Unlike many words found in Merriam-Webster, the primary definition for “tactical” is precise and explicit. Succinctly defined as “of or related to combat tactics occurring at the battlefront,” the only minor wiggle room regarding its meaning concerns the specific type of warfare it describes.

The inclusion of the adjective was once equally clear and reserved for a singular purpose in the realm of product marketing. It was a term applied to gear designed exclusively and intentionally for military and law enforcement use, often epitomized by features like pockets for pistols, knives, armored plates and bullets.

Twenty years later, invocations of the term are now both far more complex and far more common, at least in the context of manufactured goods. Yet strangely, the rise in prevalence of tactical descriptors isn’t correlated to an explosion in new military-grade products.

On the contrary, the adjective now seems to litter the blurbs of millions of increasingly benign products — think sneakers, T-shirts and pants, — targeted at similarly benign civilian activities. It’s also crept into headlines and stories scattered across a wide range of consumer media outlets, including our own website.

It’s a linguistic development that traces back to the same market phenomenon: the birth and rapid evolution of a new product positioning strategy, seeded and defined by a set of companies following different pages from the same marketing playbook.

These companies, in some cases self-proclaimed leaders in the tactical space, and in other cases focused on wider market segments, have each co-opted tactical as a short-hand term to serve their own distinct ends. For some, it describes the company’s ethos or approach to product development. For others, it’s a direct reference to its intended customer base.

Unfortunately, few self identified tactical gear brands appear to agree on what the adjective implies, or more importantly, whether ordinary civilians should be considered as customers.

The consequences of this confusion have already arguably impacted our world in divisive ways, and there’s little reason to believe things will change anytime soon.

From Active Lifestyle to Active Duty, and Back Again

What does the tactical adjective mean in 2022? For some companies in the space, the term is still closely tied to its historical roots.

One self-described tactical brand, UF Pro, defines the category as “everything from pants to plate carriers… driven by a mission and a purpose” as well as its intended customer. “In this context, we are talking about the tools and work clothes of our military and law enforcement.”

Other, seemingly more commonly accepted definitions, are far less concise.

In an 80-page market report, research agency Technavio references “a wide range of products with additional features, which include the use of lightweight and comfortable fabrics; fading, tearing, abrasions, wrinkling, heat, wind, and shrinking resistant clothes with waist tabs; and additional storage and multiple pockets.”

Viewed this way, the word “tactical” could be used interchangeably with “technical,” and it often is. The synonymous nature of the terms in some eyes speaks directly to the origins and current focus of at least one prominent brand in the tactical gear space today: 5.11 Tactical*.

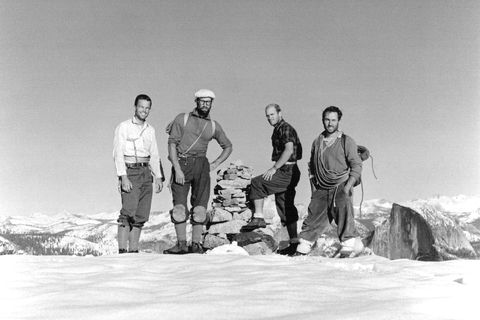

On a climb in Yosemite National Park, so the story goes, a rock climber named Royal Robbins realized the pants he was wearing weren’t quite up to snuff. Robbins was a nut for rock climbing, and he often did it with two close friends who themselves became eventual legends in the outdoor technical gear industry as well: Yvon Chouinard, the founder of Patagonia, and Doug Tompkins, the founder of The North Face.

Like the now iconic brands of his climbing partners, Robbins believed he could leverage his experience to manufacture a better product tailor-made to the specific technical needs of climbers. He, alongside his wife Liz, were already familiar with selling outdoor gear through their own company, originally dubbed Mountain Paraphernalia, then later called Robbins Mountain Gear and eventually Royal Robbins, which got its start distributing technical shoes.

In 1968, Robbins began manufacturing his own pant design. True to his background, the new pants were named 5.11, after the highest difficulty move level defined by the rock pitch rating system known as the Yosemite Decimal System or YDS, and understood by members of the community as a climbing maneuver that, at least then, proved virtually impossible to accomplish. (The rating system has grown since, making 5.15 the maximum difficulty level.)

Robbins’s company remained focused on creating both specialized, purpose-built gear and lifestyle pieces that addressed the unique needs of granola-eating climbers on El Capitan and their snowsport loving ilk, eventually launching a full backcountry clothing line that according to Robbins was “designed for comfort, fashion, originality and sense of fun” and generated $7,000,000 in annual sales by 1985.

But the functionality and ruggedness of his pants also caught the attention of a surprising customer set based in Quantico, Virginia: the FBI.

It was in this unintentional customer base that Dan Costa — a savvy hospitality executive with a highly regarded restaurant in Modesto, California, who bought the Royal Robbins brand outright in 2002 after previously purchasing a controlling stake in 1999 — saw immense opportunity.

In 2003, Costa sold the Royal Robbins name back to Robbins, while retaining the 5.11 brand to form a new company, 5.11 Tactical, with co-partner Francisco Morales. Morales, a self described “textile geek,” boasted a background in brand and product development in the sporting goods and outdoor sectors, working for brands like L.L. Bean and Dick’s Sporting Goods, and eventually assuming the role of CEO of 5.11 Tactical in 2018, a position he currently still holds.

As Morales tells the story, the FBI’s decision to adopt the pant for training helped quickly establish the brand in professional tactical circles, as visitors to the FBI’s facility from around the globe took notice of the unique khaki-colored “FBI pants.”

The feds were impressed with the product and wanted more. Soon designers from the company began working in collaboration with FBI officials via direct feedback loops to design additional garments including a vest and shirt optimized for concealing weapons and holding equipment. “I think 5.11 was the first company, by accident, that started talking to the end user [of tactical equipment],” Morales shared on an episode of the podcast FieldCraft Survival in 2019. As he explained, 5.11 was the first company to start “creating products to satisfy or meet the unique challenges that people who do what [the FBI does].”

While it gained fame for its targeted designs, 5.11 Tactical now sells regular clothing, too: hats, hoodies, polos and sneakers, through a chain of retail stores (as of September 2020) scattered across 27 states as well as at least nine other countries.

According to a company spokesperson, the brand today defines itself as “an apparel and gear brand that primarily serves outdoor enthusiasts and public safety professionals such as first responders, fire and emergency services, law enforcement and military personnel.”

This shift in product offerings mirrors a shift in the company’s customer base.

Based on 2019 financial filings from 5.11 Tactical’s current owner, Compass Diversified Holdings, who acquired the tactical brand in 2016 for $401 million, it’s estimated that 64 percent of 5.11 Tactical’s business came from the military, police and EMS — the camps Costa initially set out to serve. The rest now comes from everyday citizens. The change was a direct response to emerging trends 5.11 Tactical identified in the marketplace. “Eventually, consumers wanted to utilize the durability and technical features of those pants for other aspects and their lives. As a result, it grew in popularity and 5.11 grew its product offering,” the spokesperson shared.

The brand’s expansion aligned with changes it perceived in the way consumers interpreted the word tactical. From its vantage point, the adjective’s direct link with military-grade, combat-specific gear was fading, or at least broadening, to embody the qualities people assumed were prerequisite for military and first responder grade equipment.

As the company sees the term, “versatility is something 5.11 feels makes a product ‘tactical’ — it’s something that is durable, reliable and offers technical features that customers can depend on in all phases of life. Those are the types of products the brand looks to offer our customers.”

The strategic broadening of focus for 5.11 Tactical, who Technavio identifies as a “key player” in the market, was lucrative, too.

According to Technavio’s report, the market for what they call “tactical and outdoor clothing” today is massive, projected to hit $4.26 billion by the end of this year. (For comparison, the business consulting firm Grand View Research projects that the global snow sports apparel industry, which helped birth the original 5.11 pant, will reach $3.5 billion by 2025.) And everyone is buying. “In addition to offering clothing for military and defense, vendors are focusing on expanding their portfolios by offering tactical clothing to civilians,” the report reads.

The trend itself is clear. But the fuel for the movement — the source of tactical gear’s newfound appeal with civilian consumers — is harder to pin down.

According to 5.11 Tactical, their designs are simply meeting demand. “As technology advances, consumers’ expectation for durable products with technical features is growing… That seems to be a contributing factor in the increasing demand for tactical/technical gear.”

From Service Members to Civilians

They may be, but some are ringing the alarm. One of the first people to flag this rise in civilian interest was the National Book Award-winning graphic novelist Nate Powell, who documented what he observed in About Face, a sweeping illustrated essay he created for journalist-owned, journalist-run magazine Popula in 2019.

Powell traces the trend back to the early 2000s, when surges in voluntary service created large pools of consumers who grew accustomed to military style and sought it out in their civilian life.

“[My guess] is that it’s entirely post-9/11, and it likely dovetails with lots of the cultural rehabilitation of military aesthetic and gear,” he says. “As a new generation of soldiers returned home from Afghanistan and Iraq, those aesthetic preferences followed them and even got reinforced with post-active duty law enforcement and private security work.”

His take is supported at least in some ways by research. According to the Pew Research Center, patriotic sentiment notably surged in the immediate aftermath of September 11th. 79 percent of surveyed adults said they displayed an American flag. A year later, 62 percent of surveyed adults also said they often felt patriotic in the wake of the attacks. A majority of surveyed Americans also supported military action on behalf of the U.S. government.

New York Times Magazine writer at large Jason Zengerle deserves credit for his elegant summation of the phenomenon in his 2021 profile of the Black Rifle Coffee Company, whose current CEO, Tom Davin, served as CEO of 5.11 Tactical from 2010 through 2018, before Morales.

As he put it in the story, “before the Sept. 11 attacks, Americans who viewed the military as an aspirational lifestyle, as opposed to a professional career or a patriotic duty, were a distinctly marginal subculture, relegated to an olive-drab world of surplus stores and Soldier of Fortune subscriptions. But that changed as veterans began cycling back from Afghanistan and Iraq to a country that — while mostly removed from (and oftentimes painfully oblivious to) the realities of their service — generally admired them and, in some cases, wanted to live vicariously through their experiences.”

Many companies were quick to seize the opportunity to serve these new generations of service members and veterans integrating back into civilian society, as well as the regular civilians who admired the contributions of soldiers, police and first-responders more than ever before. And they still are, even two decades later.

Take Ten Thousand*, a brand founded by Keith Nowak, a triathlete, marathoner and former professional soccer player who set out to “create the perfect gym short” when he launched the company in 2017 — a product our team at Gear Patrol liked so much that we collaborated on a version of it in 2021.

Last year, Nowak and his team released the Tactical Shorts and Tactical Pants, designed in tandem with the Tactical Advisory Board, a team they created that comprises U.S. Special Operations Forces members — the collective title for the elite performance segments of each branch (think: Navy SEALS, Marine Raiders and Army Rangers).

According to Nowak, the products were wear-tested by 50 more active and ex-military members and tweaked until the group was satisfied. The result: products that are durable and water-resistant, with zippered pockets and less-compressive liners.

“We had no idea what to expect,” Nowak admits, “what the uptake would be within that community, [or] what it would be from the civilian population, but we were blown away by the success of it.” The Tactical Shorts are now the brand’s second best-selling product.

And it isn’t just Ten Thousand’s base buying in. Sure, a subset of the brand’s existing consumers bought pairs of the Tactical Shorts immediately upon release, but, according to Nowak, they also drove new customer acquisitions from online shoppers on the hunt for gear that matched their search queries.

“It’s the tactical guys but also the civilian population,” Nowak says. “The product itself is phenomenal. But, also, I think it’s the wear-testing story, the use-case story, the durability of the product.”

5.11 Tactical says its end-user driven approach to product development looks a lot like Ten Thousand’s, albeit without always separating professional and civilian needs. According to a brand spokesperson, “one of 5.11’s biggest differentiators in the industry is that the company utilizes end-user feedback throughout the production process — from ideation and conception throughout design, performance testing, and ultimately coming to market with a final product. 5.11 utilizes the input and experiences of professionals from all walks of life in the development of its products.”

To be clear, there’s no societal harm in making or wanting function-first clothing. In fact, it’s a developing theme in the product world we at Gear Patrol have actively championed since our inception in 2007. There are also countless professionals in the military, law enforcement and first responder fields actively serving their countries and communities who deserve equipment designed to meet the specific demands and dangers of their unique lines of work.

But the merging of these two groups over the last decade in pursuit of new customers, aided in part by an age-old marketing tactic, has started to reveal some serious side-effects.

Moving Targets and Markets

The success of Ten Thousand’s tactical line, as well as entire brands like 5.11 Tactical, are anecdotes of a broad, sweeping shift in consumer interest in the U.S.

Based on Google search query data, more Americans are actively looking for tactical gear than ever before. Searches for 5.11 Tactical’s Apex Pant? 1,500 percent. Under Armour’s Stellar Tactical Boots? 4,750 percent.

Part of the phenomenon undoubtedly mirrors trends seen in nearly every other product category, though. Products used by “pros” in any field often gain a unique mystique among casual consumers in search of best-in-class goods. In fact, it’s such a marketing cliché that Nike, Spike Lee and Michael Jordan famously made a meta-joke out of it.

In the case of tactical gear though, the general consumer’s cultural understanding of the implications of military-certified products may ironically not align with the reality of the term.

Veterans themselves will tell you that military-rooted gear isn’t necessarily better. Just ask former US Navy Petty Officer First Class Dave Weiland, who served as an Intelligence Specialist from 2009 to 2013 and a Counterintelligence and Counterterrorism Specialist from 2013 to 2015.

“Most of the stuff we wore and used in the military fucking sucked and broke all the time, so I’m not sure what that even means,” Weiland says. Yes, the military standard — abbreviated MIL-STD and enforced by the Department of Defense — can fall short, especially when products are designed to be manufactured cheaply and at-scale.

Whether or not military adoption is a true mark of quality, the question still remains: do explanations provided by the likes of 5.11 Tactical and Nate Powell fully explain the exploding popularity of tactical gear with consumers? Is it all really the result of an increased consumer desire for more functional apparel, fueled by a new generation of veterans and law enforcement and flamed by advertising strategies?

Deeper looks into the category hint that perceived improvements in product quality are, at best, only partial drivers of consumer interest. That’s because the growth trends aren’t limited to durable iterations of common clothing staples large swaths of consumers regularly use. The trends also extend to other goods normally strictly aligned more with military and law enforcement needs as well.

Take Rothco’s Lightweight Tactical Plate Carrier, a military-grade tactical vest designed to hold bulletproof body armor plates, as well as magazines of pistol and rifle ammunition, and as such, is subject to arms regulation that restricted it from being sold in some countries outside the United States. Google searches for the item increased by 300 percent over the same period. 5.11 Tactical’s version, the TacTec Plate Carrier, saw a 500 percent spike. At the same time, firearm sales in America have broken records in recent years, with a fifth of buyers being first-time gun owners.

Truthfully, it’s impossible to attribute all the macro social, political and economic forces influencing the concerning increases in civilian interest for self-defense and combat adjacent products, once reserved exclusively for members of the military or law enforcement, to a simple cause like irresponsible marketing.

Still, it doesn’t require a massive leap in logic to presume that certain marketing strategies employed by members of the booming tactical gear industry may have, at a minimum, helped fan the flames of an already raging fire.

From Functionality to Factions

Like most things that hinge on human language and perception, drawing a clear line between responsible and detrimental marketing practices in the context of tactical gear is difficult to do. Separating targeted communication to professionals with legitimate tactical needs from the more dubious, financially motivated decisions to expand a customer base to broader civilian populations, is as much a matter of gut feeling as it is clinical analysis.

However, a review of approaches employed by a variety of companies reveals a spectrum of thresholds that, when crossed by consumer brands, at least suggest a lack of concern over blurring the lines between military and civilian activities.

On one end of the spectrum sit the countless companies contracted to create tactical goods explicitly for government organizations. These companies are known only to those in the defense industry because civilian consumers are not a part of their business plans.

There are also many consumer brands that generally avoid military associations, despite making versatile, durable and/or technically oriented goods in a similar vein to some tactical gear. Examples include everything from durable workwear brands like Best American Duffel and Carhartt to technical brands like Ministry of Supply, Outlier and their competitors, and even most major outdoor gear manufacturers.

Some companies such as Alpha Industries, Randolph Engineering, G-Shock, Bell&Ross and Triple Aught Design manage to exude military toughness and market products that are deeply inspired by the military, or were even once made for military use, while steering clear of justifying their value as a response to prepping against constant threat of conflict.

Projects like Arc’teryx’s LEAF and Patagonia’s Lost Arrow, in contrast, represent one of the safest ways consumer-centric brands can still address the tactical gear market. These under-publicized projects stand as dedicated silos for each company’s military-grade equipment. They are purposefully held apart from their globally renowned consumer brands, presumably to minimize any confusion between the products and their dramatically different customer bases, though the true motivations behind their approach remain unclear.

Then there are tactical brands that choose to depict their tactical gear being used specifically by identified active military members, or known veterans with careers tightly associated with military and law enforcement agencies, versus nameless product models or explicitly identified civilians. For example, on the product page for Ten Thousand’s Tactical Pants, Navy SEALs Alex Fichtler and Mike O’Dowd are depicted training in the field with the pants, tactical packs, flak vests and firearms.

Others appear to target those with professional ties to the military and law enforcement, while also promoting their product’s value to their off-duty lives.

The page for Mystery Ranch’s popular Assault Pack illustrates this well: It features a crew of camo-clad soldiers seemingly on patrol. The names of the various packs include “Gunfighter” and “Raid,” direct callbacks to situations normally only experienced by military and law enforcement personnel.

But each pack’s description makes an effort to reference common civilian needs too. For example, the Gunfighter “can be used as an everyday backpack while still supplying mission-specific needs” while carrying “tactical gear or your laptop.” The Raid LT is framed as having a similarly versatile design that can “meet the organizational demands of mission-critical gear and every-use essentials.”

5.11 Tactical views many of its products as addressing a similarly mixed set of on- and off-duty use cases. According to a spokesperson, the company feels customers are interested in products that can “integrate into multiple phases of their lives,” whether they’re “enjoying an outdoor adventure” or “an on-or-off duty first responder,” while also acknowledging that its products can benefit “just someone living their day-to-day life” as well.

Still, many brands in the space — 5.11 included — appear to be growing more comfortable addressing civilians directly, dismissing the practice of framing tactical products only towards members with professional-based needs for such gear.

For example, among a bevy of images and messages on 5.11 Tactical’s Instagram page, which counts various consumer groups ranging from veterans and those who support them to CrossFit athletes, bow hunters and dads as followers, you’ll occasionally find unidentified, tactical pack-toting figures posing artfully with assault rifles accompanied by oblique, simple captions like “Let freedom ring.” And they aren’t alone.

The social media feeds of TRU-SPEC — a brand self-described as “one of the leading suppliers of uniforms and personal equipment to the military, law enforcement and public safety markets” — promote messages aimed at a wide swath of individuals, albeit with clearer attempts at distinguishing between tactical and more general needs.

One recent post depicts a man wearing tactical pants and a vest, equipped with a holstered pistol on his hip while pointing an automatic weapon with a caption aimed at “every officer, tech and operator.” Another post features the words “not just a tactical apparel company” plastered in bold font across the top of a triptych highlighting a variety of men hard at work. “When you think of TRU-SPEC, you most likely think tactical, but our 24-7 Series line of products are made for on and off duty applications across dozens of fields. So if you are an electrician, builder, landscaper or anyone needing durable apparel, then TRU-SPEC has something for you,” the accompanying caption reads.

Such messages are indicative samples of a wider strategy employed in varying degrees by an array of tactical gear brands. It’s an approach that acknowledges an apparent and increasingly pertinent factor behind the demand and interest for goods with tactical origins. In short, the relevance of tactical gear for many consumers now is as much about signaling one’s connection to a distinct and growing community united by a common ethos as it is about requiring equipment to address specific needs in everyday life.

At least that’s the perception of many observing the trends evolution outside the tactical community. “[It’s the] idolization of the Special Operator,” says Charles McFarlane, a writer (and former Gear Patrol employee) who runs his own military aesthetic and culture newsletter, Combat Threads.

Powell views the shift through a similar lens. “The main thing being sold here is the notion of being above the law as a stand-in for the cowboy, the rebel, the sovereign citizen,” he says.

From their vantage point, a growing customer set co-opts attire designed for Special Forces because they covet the presumed status that comes with dedicating your life to service. However, they don’t have the training that teaches them when to yield it, nor the experience to know the destruction such power can cause.

To be clear, men have long worn military-inspired garb: T-shirts. Aviator sunglasses. Dive watches. Even camouflage. But such items, first developed for use in wartime, have become benign over time. “Most camouflage today is essentially paisley — it’s an all-over print,” McFarlane says. “It’s been so taken in by fashion and by culture that it has lost its teeth as a symbol of state power or violence.”

By contrast, modern tactical gear can imply more aggressive and contrarian-based social signaling. Put differently, if wearing vintage camouflage helps people fit into mainstream culture, donning concealed-carry pants and vests with pockets for ballistic plates sets them apart.

Viewing things through this lens helps explain why tactical clothing enters the public eye in moments of instability, such as at protests and rallies. Even without a police presence, this sort of attire can give an arena meant for civilians the feel of a combat zone.

“It’s like armor,” says Tim Godbold, author of Military Style Invades Fashion, “but most of these men aren’t military-trained. They want to look like they are, and the way you can do that is by dressing like one.”

Unsurprisingly, many prominent personalities in the tactical space are quick to refute such takes on the community’s motivations and stance. In the eyes of retired Navy SEAL and crisis management expert Clint Emerson, author of the 100 Deadly Skills book series and a past 5.11 Tactical collaborator, the unifying theme of the tactical community “[isn’t] about being paranoid, it’s about being self-reliant and accountable.”

5.11 Tactical sees its intended consumer in a similar light: Its tagline is “Always be ready” and, as their spokesperson explains, this principle is what unites its growing base. “As a brand, 5.11 stands for preparedness, which includes mental strength, physical training and having durable, purpose-built gear you can depend on. Those are all principles that the company’s customer base integrates into multiple phases of their lives.”

The rhetoric has clearly resonated with an intended consumer set loosely united by the adage of “plan for the worst, hope for the best” or a reverence for the sacrifices members of the military, law enforcement and first-responders make to serve their communities.

But it’s also gained a foothold in extremist groups galvanized by alarming ideas of maintaining constant vigilance against a looming, unnamed and ever-present threat that could trigger violent conflict at any moment.

Such was the lesson for Black Rifle Coffee Company, a rapidly growing coffee company founded by veterans who served in Afghanistan and Iraq. It’s known, at least in part, for its many military and tactical references weaved throughout product line, such as its AK-47 Espresso Blend. But company merchandise has now been documented being worn by Kyle Rittenhouse, as well as a masked man who breached the Senate Chamber on January 6th, 2021.

Like the age-old question of what came first, the chicken or the egg, it’s a fruitless exercise to decipher whether loose attitudes toward tactical terminology and imagery employed by brands, and even media outlets like Gear Patrol, are the source of civilian interest in tactical products, or merely responses to their demands. The reality is likely a bit of both.

And as satisfying as it is to find a source to blame, investing time in such exercises in the case of the tactical gear is ultimately just a distraction from potentially achievable goals.

The Weight of Words

The impetus to define and corral tactical terminology and isn’t just a matter of semantic stuffiness. In this case, encouraging loose interpretations can blur civilian needs with those of soldiers heading to war.

And what might be casually dismissed by some as cosplay represents a more serious issue when recent scientific research investigating how tactical gear impacts people’s perception is taken into account.

“Findings suggest that the public harbors significant negative perceptions of certain officers donning militarized attire with regards to approachability, trust and morality, among other qualities,” Carleton University Professor of Psychology, Brittany Blaskovits, writes in an academic paper published in early 2022 titled The Thin Blue Line Between Cop and Soldier: Examining Public Perceptions of the Militarized Appearance of Police. “However, these officers are also perceived to be stronger, confident, and more prepared for threatening behavior/dangerous situations.”

Preparedness is a thread worth pulling. The notion is arguably one of the biggest drivers behind why some folks embrace tactical gear.

But if corporations ranging from mass manufacturing defense giants — like Honeywell and BAE Systems, which sell everything from planes to tactical apparel and bags, and together raked in more than $50 billion in 2021 — to world-renowned outdoor companies all choose to avoid making tactical-based appeals to civilian consumers, why are other outfitters so eager to? Why can’t the tactical gear industry frame products intended for civilians with different terminology and imagery?

Brands in the space are quick to assert they don’t market themselves toward extremists or attempt to turn everyday citizens into ones. Nor do they knowingly outfit militias. A spokesperson for 5.11 Tactical confirms that “the company is not politically motivated and does not condone any unlawful activity or violence.”

Still, using words like “tactical” too loosely, especially in conjunction with military-inspired imagery, as a way to promote gear to a mixed bag of consumers, can be a slippery slope — one that walks a tightrope between signaling technical superiority or means-testing products and stoking an audience seeking products that will vicariously elevate them into the ranks of real service members or, even worse, better equip them to carry out acts of violence.

As the Capitol riot hearings continue, we can’t help but revisit January 6th images replete with tactical gear or reread Facebook’s ban on ads promoting tactical gear in the days that followed. At the same time, we can read about the commercially available tactical plate carriers worn by the gunmen in both Buffalo and Uvalde — and many other mass shootings before them.

Marketing language or media pieces that suggests any civilian should “step up” — to “always be ready,” alongside images of firearms and other equipment used in war — runs the risk of “pushing the idea that only uniformed/armed power keeps our society from dissolving,” Powell says. As such, it’s time to consider what descriptors like “tactical” are really saying intentionally or not — and what the alternatives are.

But relying on tactical gear manufacturers alone to come to a more responsible consensus on marketing ruggedized, technical products to civilians feels highly unrealistic. That is unless all of us as consumers can vector towards a clearer collective understanding of the proverbial lines in the sand manufacturers of tactical gear shouldn’t cross.

Of course, while it’s easy to offer a call to action, there’s work to be done — and not just by brands selling consumer goods. Throughout its history, Gear Patrol has covered most if not all the brands mentioned in this piece and uplifted the word “tactical” a hundred times over in articles ranking the best backpacks, T-shirts, watches and more. In short, our outlet has played a role in the movement too. As such, we must be careful with our own words and conscious of what items actually make sense for civilian use. Language evolves, and, in 2022, we need to recognize that tactical isn’t the same word it was even a few short years ago.

Does that mean our team will never write about military-inspired packs or tactical pants again? Or that you shouldn’t buy them? Not necessarily, but we will be making a conscious effort in the future to curb the confusion caused by conflating consumer-grade and professional-level products (i.e. military and law enforcement equipment.)

This process starts with all of us, as leaders of brands, leaders in media or as individual consumers, asking one important question: Are certain words and images simple marketing hooks or more potentially concerning calls to action? We’ve already witnessed an uptick in the number of armed militias and an increase in deaths due to gun violence. As such, in a nation that becomes more divided (and on edge) with every passing day, taking time to apply a more critical eye to this matter feels more important than ever.

*Article Disclosures:

- 5.11 tactical is a former advertiser on Gear Patrol.

- Gear Patrol has collaborated with Ten Thousand on apparel and engaged in collaborative marketing campaigns.

- Charles McFarlane is a former writer for Gear Patrol.